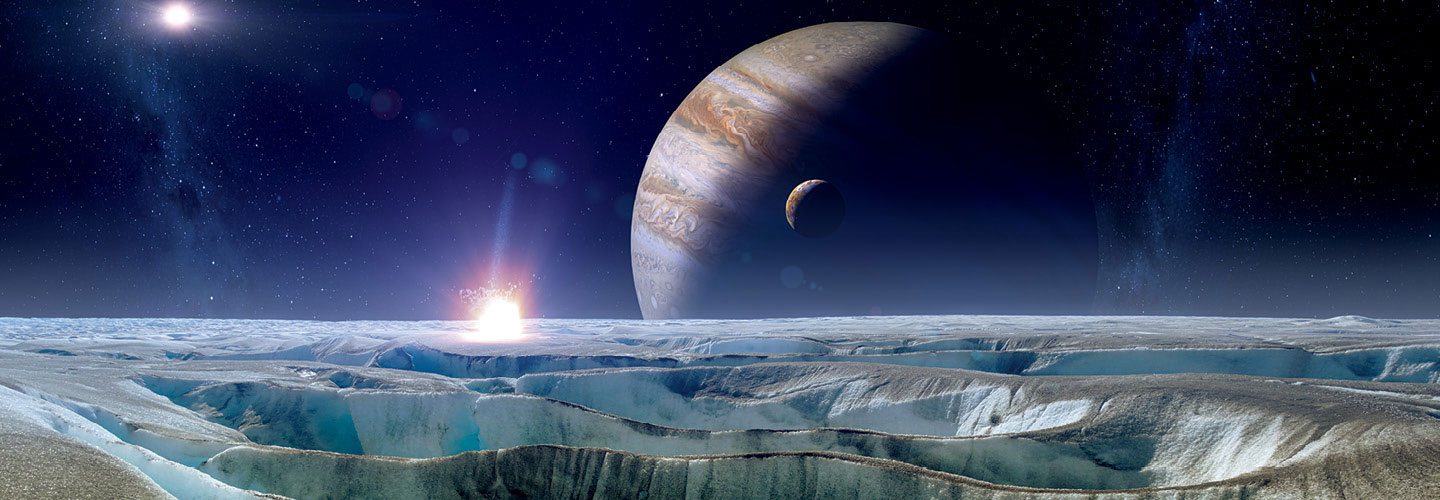

Images courtesy of NASA and the Conceptual Image Lab.

Walt Feimer

Scholastic Art: What is your job?

Walt Feimer: I am the animation manager at the Conceptual Image Lab for NASA. We create animations that are used in proposals for space missions, featured in press releases to illustrate the results of missions, and posted to our website or our YouTube channel to share new science discoveries with the public.

SA: What are you currently animating?

WF: Currently, we are working on an animation that will show a spacecraft module descending onto the surface of Venus. This animation is for a mission proposal. Missions have to compete for approval to move forward. Our animation will help show what the scientists hope this mission will accomplish. The proposal will go through an internal review to determine whether the mission will actually happen.

SA: What else have you animated?

WF: Lots of things! Our animations include a massive black hole shredding a star; the evolution of the moon; water vapor erupting from the surface of one of Jupiter’s moons; solar flares; spacecraft on their missions; and instruments in action, such as collecting a sample from an asteroid; and much more!